2nd-5th century CE, exact date unknown. First Chinese Translation 5th century CE. “The Diamond That cuts through illusion” or the Vajra Cutter Perfection of Wisdom Sūtra” (Vajra – thunderbolt, diamond, adamantine weapon). This is a key Mahāyāna Sutra from the Prajñāpāramitā family of texts.

Very popular in Chinese tradition as: 金剛般若波羅蜜多經, Jīngāng Bōrě-bōluómìduō Jīng; shortened to 金剛經, Jīngāng Jīng.

First Chinese translation is thought to have been made by Kumarajiva (鳩摩羅什, Jiūmóluóshí) : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kum%C4%81raj%C4%ABva. Also translated by Xuanzhang.

From Wikipedia

The Diamond Sutra (Sanskrit: Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra) is a Mahāyāna Buddhist sutra (a kind of holy scripture) from the genre of Prajñāpāramitā (‘perfection of wisdom’) sutras. Translated into a variety of languages over a broad geographic range, the Diamond Sūtra is one of the most influential Mahayana sutras in East Asia, and it is particularly prominent within the Chan (or Zen) tradition,[1] along with the Heart Sutra…

The Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sutra contains the discourse of the Buddha to a senior monk, Subhuti.[12] Its major themes are anatman (not-self), the emptiness of all phenomena (though the term ‘śūnyatā’ itself does not appear in the text),[13] the liberation of all beings without attachment and the importance of spreading and teaching the Diamond Sūtra itself. In his commentary on the Diamond Sūtra, Hsing Yun describes the four main points from the sūtra as giving without attachment to self, liberating beings without notions of self and other, living without attachment, and cultivating without attainment.[14] According to Shigenori Nagatomo, the major goal of the Diamond Sūtra is: “an existential project aiming at achieving and embodying a non-discriminatory basis for knowledge” or “the emancipation from the fundamental ignorance of not knowing how to experience reality as it is”.[15]

In the sūtra, the Buddha has finished his daily walk to Sravasti with the monks to gather offerings of food, and he sits down to rest. Elder Subhūti comes forth and asks the Buddha: “How, Lord, should one who has set out on the bodhisattva path take his stand, how should he proceed, how should he control the mind?”[16] What follows is a dialogue regarding the nature of the “perfection of insight” (Prajñāpāramitā) and the nature of ultimate reality (which is illusory and empty). The Buddha begins by answering Subhuti by stating that he will bring all living beings to final nirvana, but that after this “no living being whatsoever has been brought to extinction”.[16] This is because a bodhisattva does not see beings through reified concepts such as “person”, “soul” or “self”, but sees them through the lens of perfect understanding, as empty of inherent, unchanging self.

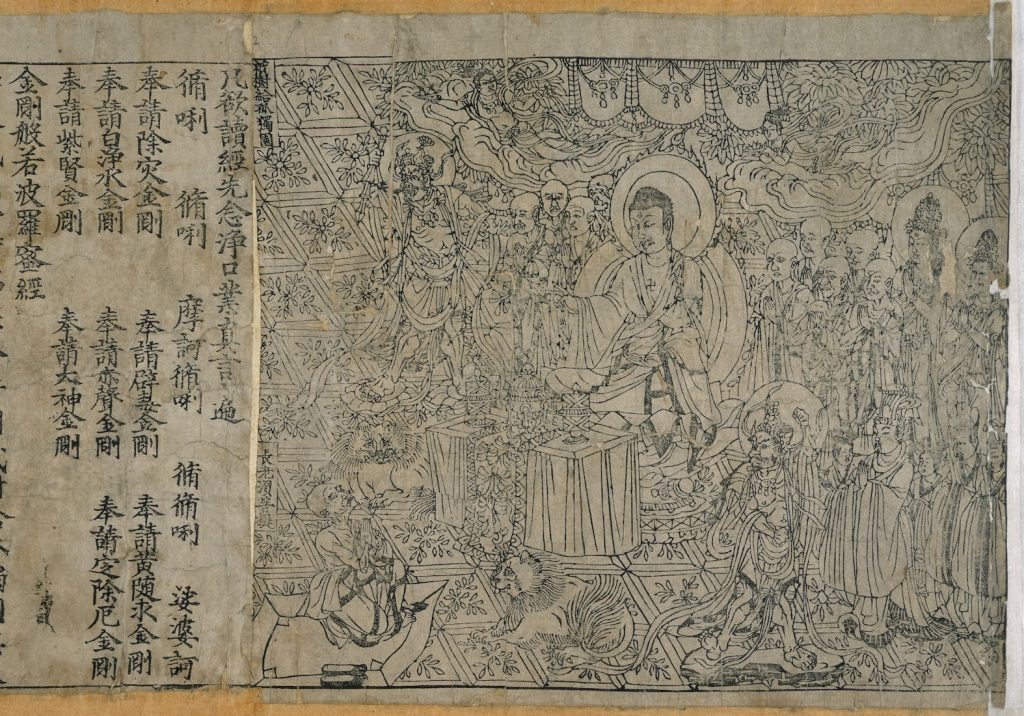

Frontispiece, Diamond Sutra from Cave 17, Dunhuang, ink on paper. A page from the Diamond Sutra, printed in the 9th year of Xiantong Era of the Tang dynasty, i.e. 868 CE. Currently located in the British Library, London. This sutra was discovered at the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, but probably printed in Sichuan (see “Printed dated copy of the Diamond Sutra“). According to the British Library, it is “the earliest complete survival of a dated printed book”.